On becoming a writer

Albie on becoming a writer

There are two things I remember with the most pleasure of my years at school. The one was the debating society. I loved debates and discussions. The other was working on the school magazine. That was real pleasure, editing it, writing for it, reading things that other people had done. The art of writing then wasn't writing about deep experience, finding a way to communicate something. It was about being clever, being smart. It was using language in an intelligent and subtle way, and I'm glad I did that, I'm glad I did the exercises, I'm glad I learned about the vitality and elasticity of language, and that I invested a lot of my thoughts, and my thinking into those things.

I've had quite a few unusual experiences in my life, but one of the strangest of all was my first day at school when the teacher had a big piece of cardboard, and there were some letters on it saying, 'The cat sat on the mat,' and we had to say, 'The cat sat on the mat.' And I wasn’t sure why we were doing this. I was reading books. I must have learned to read and write in the kindergarten, where we didn't have teachers telling us to say, ‘The cat sat on the mat’ ten times.

The fact is, I can't remember a time when I didn't have books. They just seemed to be around. And some of the most interesting hours of my young life were reading. We would get comics by mail, shipped from England, and they would usually depict the story of a schoolboy from a poorly family going to quite a posh school and the tensions created there and putting up with bullies and finding companionship. And it was lovely reading those stories.

My brother and I would spend two holidays a year in Johannesburg. The teacher would ask the class to write letters about what we did in our holidays. I described a thunderstorm in Johannesburg. It came out of the blue. I enjoyed trying to capture the sounds of nature, the gurgling feeling, the running water. It wasn't a story where anything happened other than nature was disporting itself in a very extravagant sort of a way, and I remember the teacher was very pleased.

I'm not sure when I discovered novels. I think it would have been my first year at university, maybe my last year at school. For some reason I never really took to English novels. The only English novel that I remember enjoying was Vanity Fair by Thakur Ray. It had ambiguous characters and was somehow more interesting. The breakthrough came with Russian writers; the most passionate, Dostoyevsky. Breathless, I couldn't wait to read more. And then at the age of 20 I read Tolstoy. I was in England, visiting in Manchester. It was very cold. I had War and Peace, and I read it in one weekend. I was captivated internally by the language and the unexpectedness of the story, and what was happening to the characters.

French novels captivated me after that, and short stories as well. And maybe I wanted something exotic. I would never dream of reading a novel set in South Africa. Novels belong to the world of imagination, not science fiction, which I've never enjoyed and never got into, but a literary world that was so intense and powerful. It's as though the world of novels was more real than the rather banal world in which we lived.

I knew a writer, his name was Uys Krige. We'd stayed, my mom and her two little children, in a basement of a bungalow that he then owned in Clifton. And I remember being told he was a poet, and I couldn't understand; what was a poet? I could understand an engine driver, I could understand a pilot, I could understand a doctor, I could understand a nurse. But what does a poet do? And I felt a poet does things with words, but we all do things with words. I couldn't imagine it being an occupation. Words were like the air you breathe, it's what you do, it's how you live.

We were compelled to study Afrikaans as a second language, and to read Afrikaans literature. But the literature that was chosen would be about animals. Anything about people raised questions of nationalism and British conquest and so on. And we hated those books. It was partly a sort of English disdain for that language which we felt was being forced upon us, partly because we didn't want to read about lions and baboons and ants. We wanted to read about rugby players and boxers and pilots of Spitfires that Hurricanes that shot down, you know, the enemy. I mention that because years later, when I was in exile in England, I remember those Afrikaans books, and I think because those books were written by people feeling they were in internal exile in South Africa. The British are controlling not only the economic life, but the cultural, imaginative life. So, through writing about animals, they could escape that British domination and write with a great fidelity and richness and subtlety about the life of lions and the life of baboons and even the life of ants.

I read Jules Verne Journey to the Moon, and I knew when I'm big, I'm going to be somebody going in a rocket to the moon. Then I read a book about Louis Pasteur, and now I knew I'm going to find a microbe smaller than Pasteur ever found. So that world of fiction captivated me, and the idea of being a writer appealed to me very much, being able to not only read what other people have written, but to write things that other people will find interesting.

So, in the back of my mind was the idea that I didn't know what I would do when I grew up and went out into the world, but I'd like to become a writer. I'd like to create something in words, in language, to tell stories in ways that people would find interesting.

Instead, I became a lawyer. It was reading Darrow for the Defense by Irving Stone. A beautifully written, powerful story about this brave lawyer standing up to agents of power and negativity and oppression through the courts. And I'm sure it was reading that made me decide not to become a doctor, to look for the smallest microbe ever found, or an engineer flying to the moon, but to become a lawyer.

Writing in legal language wasn't easy, it wasn't automatic. It's almost like it's a whole other language. It's a way of saying things, making statements, that follows a certain tradition and logic and form of communication that is very meaningful to everybody who belongs to that club, who is familiar with that language. And we would be corrected for using adjectives that didn't belong, descriptive things that weren't necessary for the telling of the propositions that we required. And then when I had to write legal opinions it required such intensity of focus, there was no scope for imagination. You had to just get it right. You had to know the logic and follow the logic of legal reasoning. So, in that sense, legal writing became the enemy of imaginative forms of storytelling. And I put so much into my legal writing. It might be giving legal opinion, it might be preparing an argument for an appeal, it might be preparing for cross examination. It required another kind of imagination, but it would be legal imagination. And I felt a certain sadness that a side of me that I would have maybe liked to develop just wasn't being developed.

But in between, I'd done courses in English at the University, and they had a special course for lawyers. You could do English as a subject for a BA Bachelor of Arts, and you could major in it. Alternatively, you could do what was called English special which dealt with modern theater, as I remember, contemporary life, and modern poetry; and I loved it. I loved reading WH Auden. It was precise, it was accessible, and it was about contemporary things. I loved reading Wuthering Heights, the novel by Emily Brontë, and I loved reading Hedda Gabler and The Wild Duck by Henrik Ibsen.

I remember when I had to write an essay on Wuthering Heights, I described the main character as representing a surreal force. And the professor marking the paper said, ‘Where did you get this from?’ I said, ‘This is just my understanding,’ because at that time I was investing myself in understanding modern art, going through pages and pages at the bookshop, coming across surrealism, studying, looking at art and seeing the connections. And I realised that the main character represented a certain almost subterranean force, not just an ordinary person in a family behaving in an ordinary way. So, I got the gold medal for English. It had been unheard of for a lawyer doing English Special to get the gold medal. It went to the people studying English to become English teachers, and maybe writers.

The second year was Shakespeare and Anglo Saxon; so tedious, and I never really got into Shakespeare. Why? I was involved in the struggle. It was Shakespeare or revolution, not the two together. I had volunteered for the Defiance Campaign. My imagination, my heart, my spirit was elsewhere.

The only other thing that gave me some hope for something of a literary vocation one day was we had a course called Classical Culture, and it meant knowing Latin. We would study Virgil and do translation from the Iliad into English. And a young teacher asked us, 'Which poet did you prefer Virgil or Catullus?' My thinking was that the struggle is something grand, and about transformation and change. So, to his disappointment, I chose Virgil. But one of my translations was held up by the lecturer because it wasn't just translating the words, it was finding a poetic way in English to capture what had been written in Latin. And I had my 15 minutes of fame in that class. One of the girls I was quite keen on came to me and her eyes were wide… I was just hoping she wouldn't ask me how old I was, because I was only 16, and she would have been 18.

The other writing I did was as a journalist. On Friday afternoon, I would go up to the New Age weekly newspaper. I would cull materials from left wing journals that we received from all over the world. So, it wasn't original writing, but it was doing a headline, and I loved the layout of the page. It was reporting from the world. It was making the readers feel in touch with the world outside.

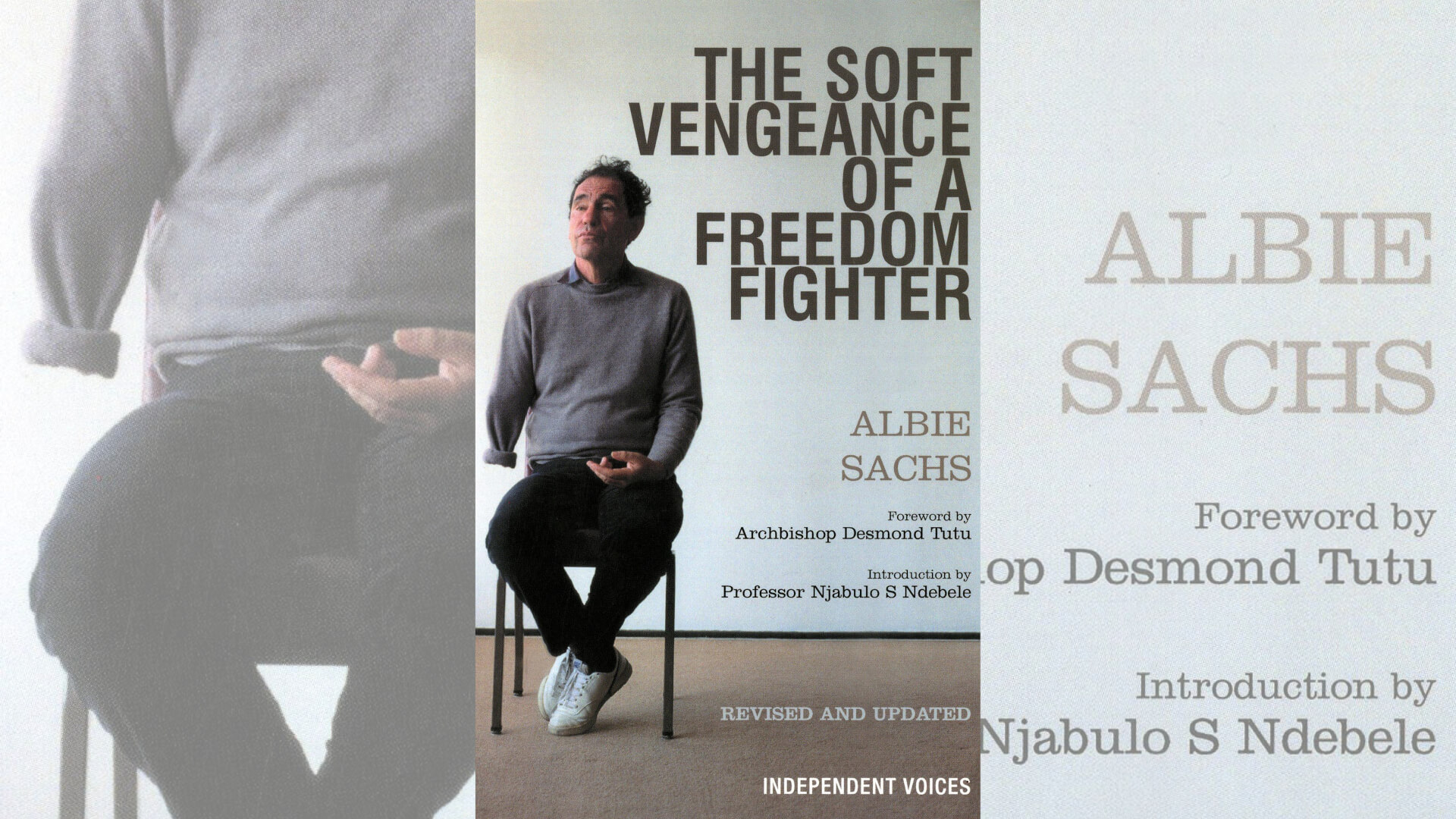

And it brings me to what I'm going to deal with next, how I'm locked up, I'm in prison, I'm having the worst time of my life, and I'm trying to think of something nice in the world. And I imagined I could write. I could write a book out of that evil, the awfulness of everything; something positive could come out of it.

Scroll for more